Free software and inspection are key to software we can trust

Posted on Sep 30, 2022 byInspecting software is essential for understanding what that piece of software is actually doing. And free software means that all users have the guaranteed opportunity to fully inspect the source code they rely on. The cyber-security industry is built on inspecting software to find malware and build up defenses. Malware scanners use large collections of characteristic signatures of software to scan billions of devices, while finding new attacks requires code audits, technical analysis, and forensics. This is the most well known field of software inspection. There are also volunteers, academics, and civil society organizations looking for tracking, targeted attacks, addictive dark patterns, surveillance capitalism, and other unethical practices. The F-Droid community is also built on inspection, making sure we ship free software and mark Anti-Features.

Some developers will describe the features, but leave key details out. This can be just a simple oversight, or they might know that users will be unhappy, so they aim to keep those details out of the public eye. Even developers who are working hard to be transparent and honestly serve their users can be ensnared. We have huge industries telling developers to include all sorts of libraries and services in their apps because it will improve the functionality or development process.

- “Finding opportunities to generate revenue shouldn’t be difficult!”

- “Great data collection software enables you to maximize productivity!”

- “App monetization is a way of helping you make money from your mobile app without charging for it.”

Those often include things that users do not want. What those industries are actually saying is: gather as much personal data as possible, track the users, hook them addictive dark patterns, and demand their attention to show them as many ads as possible. These are what we are working to expose, and building tools so we are more effective and more people can get involved.

Scanning with signatures

One of the most reliable methods for human inspection of software is to automatically apply signatures of interesting features to present to a human reviewer. The signatures can be chunks of binary machine code, URLs, function names, domain names, or bits of metadata like API Key IDs. Binary code signatures are the main method used by all sorts of malware scanners. Malware researchers work to find small patterns that are unique to that specific malware, but not found elsewhere. Here is an example of such a signature, it is the YARA profile for the Silentbanker trojan:

strings:

$a = {6A 40 68 00 30 00 00 6A 14 8D 91}

$b = {8D 4D B0 2B C1 83 C0 27 99 6A 4E 59 F7 F9}

$c = "UVODFRYSIHLNWPEJXQZAKCBGMT"

condition:

$a or $b or $c

F-Droid also uses signatures to help app maintainers find Anti-Features and

block non-free bits. The oldest version of this is the command line tool

fdroid scanner. F-Droid’s founder, Ciaran Gultnieks, added a scanner to

find some “usual suspects” over ten years

ago:

# Scan for common known non-free blobs:

usual_suspects = ['flurryagent',

'paypal_mpl',

'libgoogleanalytics',

'admob-sdk-android',

'googleadview',

'googleadmobadssdk']

Exodus Privacy has built a large collection of profiles on tracking companies. ETIP is their platform for creating and managing profiles of trackers. Data is entered and maintained there, then as given profiles are proven accurate enough, they are added to the official Exodus dataset. These profiles include signatures for automatically detecting the trackers in the APK files that are installed onto your device when you install an app. F-Droid has used the Exodus profiles indirectly for a long time now.

id: d25d820d-4c97-420e-a7d7-72434c58a575

name: ABTasty

description: |

You can use this library to access AB Tasty endpoints, which can

generate a unique visitor ID, allocate a visitor to a test, and push

visits and conversions events in order to help you analyze the

outcomes of your campaigns.

documentation:

- https://developers.abtasty.com/android-sdk.html

is_in_exodus: true

code_signature: com\.abtasty

network_signature: abtasty\.com

api_key_ids:

website: https://www.abtasty.com

maven_repository:

- https://sdk.abtasty.com/android/

- https://dl.bintray.com/abtasty/flagship-android

- https://dl.bintray.com/abtasty/Android-sdk

group_id: com.abtasty

artifact_id: librarybyapi

gradle: com.abtasty:librarybyapi:1.1.0

@IzzySoft has been maintaining the F-Droid repo for “almost free” apps. It includes its own signatures for detecting Anti-Features that might not be allowed in f-droid.org, as well as another line of defense for detecting the more general Anti-Features like Tracking.

anti_features:

- NonFreeDep

- Tracking

code_signatures:

- com\.heapanalytics

description: |-

automatically captures every web, mobile, and cloud interaction:

clicks, submits, transactions, emails, and more. Retroactively

analyze your data without writing code.

license: Proprietary

Plexus is a project of the Techlore community project for mapping out which apps work on “de-Googled” devices, and which apps work with the microG free software replacement for Google Play Services. They gather the results of tests run by humans into a machine readable format. Although it relies on human testers, not on automated pattern matching like most of the other projects mentioned here, the resulting data has a similar structure, and can be consumed in the same way in generating reports, like with issuebot.

Application: The New York Times

Package: com.nytimes.android

Version: 0.0.0

DG_Rating: X

MG_Rating: 4

DG_Notes: X

MG_Notes: Can't login with Google

Mobil Sicher also reviews apps, with a focus on Germany. They have an impressive system to do dynamic analysis of apps to find exactly what services they use on the internet. And with that data, they can mark not only trackers, but whether an app sends personal data to third party services like ad companies, cloud services, etc.

Our partners also use signatures, let’s join forces!

As we talked with various organizations about their signature collections, and applied some of them to the f-droid.org collection of apps, it became clear that there is a lot of shared structure. But each system was set up in a way that each look foreign to the others: Python code, Django admin panels, email submission, etc. If other contributors want to come in and make a contribution, they must understand each project’s format. That can be time-consuming, and there is no standardized format to follow. Then @pnu of Exodus Privacy proposed to rewrite their editing system as files in a git repo. This was the spark that made it clear that a git repo of human-editable data files would apply to all these data sets.

Based on this idea, we have launched F-Droid SUSS (Suspicious or Unwanted

Software Signatures). It is F-Droid’s collections of signatures to detect

Anti-Features in Android apps. SUSS is the first live project, and the

fdroid scanner tool will use

it. SUSS is

based on YAML files, one file per profile. YAML is basically structured

data that is meant to be human edited (all valid JSON is valid YAML even).

YAML is also widely understood since it is used in F-Droid’s own metadata

.yml format, GitLab CI, GitHub Actions and FUNDING.yml, and many more.

Additionally, it is well supported in all sorts of editors, including syntax

highlighting.

This is a step towards better integration with other organizations that share goals with F-Droid. Standardizing can reduce friction for sharing and collaborating because there is common tooling, common data formats, and automatic interoperability. This base architecture should be flexible enough to leave maintainers of these data sets to create and maintain profiles as they see fit. The standardized tools should not force people into counterproductive patterns. This project reviewed data sets from Exodus/ETIP, IzzySoft, MobilSicher, F-Droid, and TechLore Plexus. Each had distinct and specific tooling and workflows. But the rough shape of the data matches a common pattern across projects.

There is a good precedent for this kind of standardization: YARA. It is a malware signature tool started by one company and now used by dozens. That aspect of YARA applies directly to the collections of public interest signatures discussed here. Once a standard catches on, it not only increases the universality of the data, which makes it easier to use. This then can attract more users and contributors. YARA was designed around desktop malware, and unfortunately works poorly for Android. Part of that is because they made YARA be a custom format that is implemented in the YARA tool. This setup does make YARA rules simple and readable, but has big downsides. YARA is implemented in Python, so using it in other languages means re-implementing it from scratch. Android APKs are always a ZIP, unlike desktop software binaries, which are generally uncompressed files. The YARA tool devs decided they don’t want to include code to run scans on ZIP, XML, etc. So that leaves YARA hobbled for use as an Android scanner.

What do shared signatures and profiles look like?

To show what this looks like in practice, we can take an example from

fdroid scanner above. The flurryagent signature in current scanner is

used to scan through the dependency declarations in Gradle files, which are

the standard configuration for build Android apps, and files in a standard

JAR library. The Gradle

coordinate

com.fasterxml.jackson.core:jackson-core:2.11.1 would not be flagged, but

this pattern would also miss the Gradle line

com.flurry.android:analytics:10.0.0@aar. But if a JAR is included in the

app, it would be scanned, and com/flurry/android/FlurryAgent in that JAR

would produce a match. But it just outputs files with hits with no context

about what or why. As part of SUSS, each entry now gets a full featured

profile in its own YAML file, where each scan signature is distinctly

declared. That metadata then can provide more context when there are

matches.

name: Flurry

website: http://www.flurry.com

code_signatures:

- com.flurry.

network_signatures:

- flurry\.com

api_key_ids:

- flurry\.com

- com\.flurry\.admob\.MY_AD_UNIT_ID

gradle_signatures:

- com\.flurry\.android

license: NonFree

anti_features:

- Ads

- NonFree

- Tracking

In SUSS, we can now represent the fdroid scanner signatures with the

flexibility of Exodus Privacy signatures. This adds additional scans,

including domain names and the names used to declare

API

keys. fdroid

scanner had an additional allowlist, in case some signatures produced false

positives. The allowlist has been removed in favor of pure regexs (regular

expressions). The allowlist makes the F-Droid implementation quite a bit

more complicated, and ties our signature profiles to the fdroidserver

tools. The other data sets we looked at all used just simple entries,

mostly using regexs, so it is important to explore if that can cover all the

scanning cases needed. If it works out, then the path to standardization is

clear. Yes, regexs are complicated and can be painful, but they are also

widely used, implemented, documented, and understood.

One big upside of only regexs is that SUSS has a super fast, simple test suite. Here’s one way to work with it:

- Find the Gradle coordinates that are relevant and add them to the matches and exceptions lists in tests/test_suss.py

- Make the tests run once a second (with color!):

watch --color -n1 pytest-3 --color=yes - Edit the regex, for example, in suss/com.mapbox.yml

Since this only uses regexs, this test suite doesn’t need any fdroidserver code. This all would also be trivial to use in Javascript, Ruby, Rust, Java, Kotlin, etc. since the profiles are YAML and the signatures are regex.

Applying signatures

The issuebot that runs on

fdroid/rfp and

fdroiddata now

uses signatures from Exodus Privacy ETIP, fdroid scanner, and Plexus. It

is now easy to use ETIP signatures in issuebot modules, to enable

experimentation in how things should be scanned. Here are some snippets of

issuebot flagging things based on these signatures.

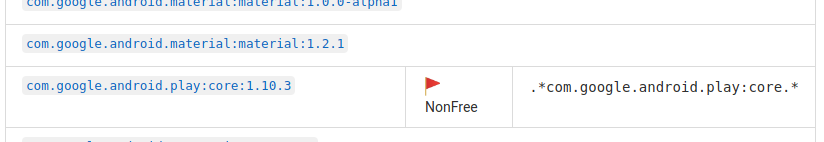

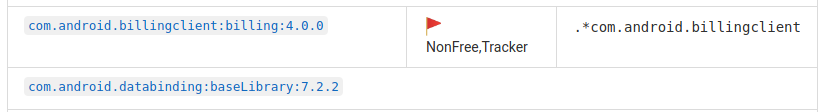

This is clearly a non-free dependency, it is required for all builds of this app.

This is a double whammy: non-free library that is used for tracking!

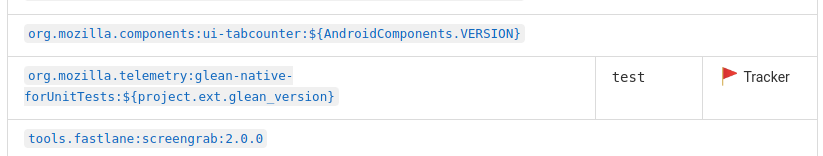

It is a match, but is the “test” flavor relevant?

There is a good match, but the library is included in the “play” flavor, and that flavor is obviously not meant for f-droid.org.

The issuebot report has many sections, based on the scan that was done. When a section has some entries that are flagged, then that section will default to being open. So these sections will be readily apparent on first read, but can always be hidden after reviewing.

There are now active methods for finding domain names and URLs in binary

APKs. The network signatures are used to check those for matches. There

are also now alternate methods of scraping the data out to then run

signature matching on. There is a new Gradle Dependencies module which gets

the full list of dependencies from either gradle/verification-metadata.xml

if present or generatable, or ./gradlew androidDependencies, if all else

fails. It then applies the code signatures to flag Gradle coordinates.

There are now multiple, overlapping methods for scraping the libraries used,

both from source code and binary APKs. These can be merged if we can

determine there is a single method that reliably finds all the dependencies.

Future Work

This project has resulted in marked improvements in the existing issuebot setup, and set up a structure for cross-project integration. We hope this data layout and a workflow that can serve as a template for other related work. Now it is launched and in action, we welcome feedback on what is working, and what is not. And contributions for improving any piece of this are always welcome. F-Droid SUSS is now a really easy way to get started, anyone who can edit basic YAML and submit a merge request can now help F-Droid improve our inspection process. Here are some low hanging fruit that are left over from this project:

-

One downside of using multiple collections of signatures is that it becomes harder to find where to edit and manage profiles. Some good UX design can help a lot there. For example, when there is a match, the UI can show a direct link to edit the profile, to make it easy for fdroiddata maintainers to fine-tune the profiles, even if they are maintained in Exodus Privacy or elsewhere.

-

We have prototyped converting the MobilSicher and IzzySoft data into the SUSS format. Once SUSS settles down as a format, we can easily convert those data sets into this format.

-

Some of the issuebot reports can still be quite long. @IzzySoft’s module’s reports are a good example of how to handle that: show the flagged things directly, then the rest goes into a linked report that is stored in the artifacts that is only loaded on demand.

(This work was funded by NLnet under an ongoing project known as Tracking the Trackers and The Search for Ethical Apps under the umbrella of Guardian Project)